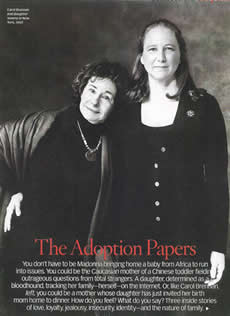

The Adoption Papers

“In 2006 my daughter Joanna, adopted at birth, now the married mother of 3, found her birth mother. That she chose to make me a full partner in the reunion gave me deep joy. That things went how they did was a minor miracle. The Other Mother, in which I shared that day and what went into it, was one of O Magazine’s top 10 articles of 2007.”

Wednesday night, January 12. I walk into the apartment, home from a not good play. Eamon looks up from his computer screen, blows a kiss, and says Joanna wanted me to call her if I got in by 11 or so. "Something the matter?"

Wednesday night, January 12. I walk into the apartment, home from a not good play. Eamon looks up from his computer screen, blows a kiss, and says Joanna wanted me to call her if I got in by 11 or so. "Something the matter?"

"Not that she said."

But my suburban, mother-of-three daughter does not invite a call at 11 on a school night just to chat.

"Hi, honey, what's up? Anything wrong?"

"No, nothing wrong. I've found her." Omigod! With no preamble about who "her" is, I know.

Words I said 40 years ago fill my head: "...and I was a mommy waiting for a baby because I couldn't grow one in my tummy. This other lady could grow a baby, but she wasn't a mommy, so I got to be your mommy. Lucky me!"

The adoption story I told each of my two kids was true as far as it went, a comfy way to explain something far from comfy. I recall 4-year-old Richard in the tub looking up at me, saying, "Too bad for her; she missed a good kid." And for sure she did. Joanna, incisive even at 3, would ask, Why? Why wouldn't a baby grow inside me? How come the other lady couldn't be a mommy? I'd answer as well as I could—analogies with gardens and soil and such, plus a few don't-knows. I didn't mention my two successive miscarriages or the recurrent dream that plagued me for years after: searching frantically for a baby I'd put down somewhere, knowing that it was hungry, hearing its weakening cry....

"Mom?" Joanna's voice in my ear.

"Wow," I manage. "So...how? Where is she? God, this is...exciting." It was—along with terrifying and a lot else. From her teen years on, when I would raise the search issue (because I should? because were I an adopted child, I'd search my head off?), Jo's stance was "I have enough family, Mother," sometimes accompanied by a blue-eyed whammy discussion closer. Suddenly (maybe not suddenly?), at 42, there's been a shift. "I...I didn't know you were looking," I say weakly. "What changed?"

"I don't know—I guess I felt ready to deal with...whatever." Scary as "whatever" might be, I nod. No question her life's in fine shape: married to a soul mate, mother extraordinaire, camp director, benefit auction ace, she and middle son Steven are also about to win Tae Kwon Do black belts.

"I didn't tell you earlier," she says, "because...well, what if I couldn't find her?" This linear logic is quintessential Joanna. She goes on to report how she summoned an online "search angel" specializing in California (Google up "search angel" to find them: many are volunteers—some adopted children or birth mothers themselves) and relayed the data she had. "You know, Mom: name, date, place—that's all you need with the databases today...."

As she explains, my mind flashes backward.

August 22, 1962, Lawton, Oklahoma: We live in a little house near Fort Sill, where my first husband was drafted the minute he finished his ob-gyn residency in New York. Eight-thirty A.M., he's left for the post hospital, Richard for nursery school, and I'm in a gray mood: Our fragile marriage, cut loose from its accustomed moorings, has developed cracks.

And then the phone rings to announce a miracle. A New York doctor we don't actually know has a pal at Mount Zion Hospital, San Francisco, who has just delivered a baby girl whose birth parents want to give her up to a good home.

The New York doc says, "I hear you've got a 3-year-old adopted boy and thought..."

"Oh God, yes! Look, I am calling for flights the second we hang up. Please, please tell them not to give her to anyone else!" Shaky marriage or not, I, who grew up in an all-girl family, ached to have a daughter.

I'd wanted to call her Joanne; my husband thought a final a added a lilt. So the fair, velvet-headed baby who slept halfway across the country in my arms became Joanna. Only later, when adoption papers arrived, did we learn that her birth mother's name was Joanne. I say coincidence—not that I haven't wondered....

Now Jo is telling me that Joanne, long divorced from birth father Bill, has gone through more men and marriages than I have—and has another daughter, five years older than Jo, by an early husband. Detail by detail, the shadow is taking solid shape and taking my breath away with her realness. She is happily remarried to Merrel, a retired navy man. They live (for which my heart offers thanks) clear across the country. They are archers; they fish. Her passion is quilting. As Joanna continues, I cannot help but feel the joy of a woman out in Oregon as she receives her miracle via e-mail, "Were you, by any chance, living or passing through San Francisco in August 1962?" and runs to her husband shouting, "I've found my daughter!"

Now Jo is telling me that Joanne, long divorced from birth father Bill, has gone through more men and marriages than I have—and has another daughter, five years older than Jo, by an early husband. Detail by detail, the shadow is taking solid shape and taking my breath away with her realness. She is happily remarried to Merrel, a retired navy man. They live (for which my heart offers thanks) clear across the country. They are archers; they fish. Her passion is quilting. As Joanna continues, I cannot help but feel the joy of a woman out in Oregon as she receives her miracle via e-mail, "Were you, by any chance, living or passing through San Francisco in August 1962?" and runs to her husband shouting, "I've found my daughter!"

My daughter: on the brink of exploring her native land, left at birth to come to mine. For the first time in a long while, I feel deep regret that I couldn't originate my children. But here's the thing: The children I have in mind are the ones I've got. And through no feat of medical science could I have born this Richard, this Joanna.

My daughter has blonde shampoo-commercial hair, Scottish blue eyes, and a temperament of measured emotion. My hair is dark and willfully curly, eyes hazel, disposition Mediterranean mercurial. We are opposites in talents and tastes. Joanna, who grew up on Central Park West, has never been a city girl, while I, a suburban kid, couldn't wait to get to New York. She loves crafts, wilderness camping, science (fact and fiction), any flying ship. She would have loved to be an astronaut, spent a few postcollege years in the air force before she married. I'm an actress turned entrepreneur, a theater and art hound, zestful downtown shopper. I neither sew nor knit. I strap into an airplane seat with white knuckles—and let's not even discuss camping.

No surprise that we were often at loggerheads. We're both stubborn: Jo's weapon is silence, mine overarguing. But our bond is stubborn, too—and precious despite snags and scars. I mostly stopped urging her to use "a little gloss and blush at least," while she began enjoying the odd browsing and lunch date with me. And it was Joanna who, with great patience, launched me on a computer to write my first novel.

Since she found Joanne, Jo and I talk almost daily. She senses how badly I need to be her partner in this; she's letting me in. Does it serve her need, too? I hope but can't swear. Friends advise me to step back, remind me it's not my search, how I'm likely to get hurt. I admit they may be right, but for me the worst pain would be exclusion. Highlight or disaster, I'm too heart-bound to sit this out.

Forwarded e-mails provide factoids that crisscross Joanne's family landscape: Crohn's disease, which could be related to Jo's own skittish stomach; foot problems, which already make Jo miserable in anything more restrictive than sneakers. More serious, the older half-sister has multiple sclerosis—in remission, but still.... When Joanne's photo lands in my in-box and clicks onto my screen, the fair, blue-eyed face of my daughter in special-effects age makeup brings tears to my eyes and triggers another flashback:

A 7-year-old girl sits with her mother facing a school counselor who is concerned about the child's reading sci-fi on her lap rather than attending to the second-grade lesson. "Why is that, Joanna?" the counselor questions.

"I like my books better," my daughter answers. "In sci-fi anything can happen." She switches her glance to me: "Mom, could you dye your hair blonde—or maybe get a wig?"

March. I'm piecing together a picture: an openhearted woman with hard miles on her, an energetic optimist who acquired the skills to earn her own living but put her trust in some disastrous men. Case in point: Jo's birth father, Bill, a bartender with dreams of becoming a chef. A charmer, he'd also been a serious drinker. Joanne had wept her heart out at his insistence that she give up the baby, yet she'd stayed with him for two more years, until he went on to father another child by someone else. Bill died of pancreatic cancer almost a decade ago—according to Joanne, brought on by drink.

Joanne has sent Jo a star quilt: Made especially for Joanna with love from Joanne. "She's making one for each of the boys, too." The delight in Jo's voice can't be missed, which begins to make me uneasy. A flash of jealousy? Sure—but also a new fear: This stranger could seduce, then wound my girl. "She asked me if you'd like a quilt, Mom—and if you like butterflies. She's been collecting these neat scraps for years. Wings."

"Yes," I say after a beat, "I think I'd like that a lot." Then I take a step. "Would it be okay with you if I e-mailed her?" Jo says sure, without a nanosecond's pause. Her trust in me makes my day.

"Yes," I say after a beat, "I think I'd like that a lot." Then I take a step. "Would it be okay with you if I e-mailed her?" Jo says sure, without a nanosecond's pause. Her trust in me makes my day.

...I want to say some things about Joanna that she wouldn't say about herself. She's a remarkable woman: resourceful, smart, fiercely loyal, kind—moral in a way that has nothing to do with organized religion and everything to do with the golden rule. My husband, Eamon, says Jo "has no side to her," meaning she's right out there, no games, strategies, or deceits. This can make one vulnerable. On the other hand, she's someone who can take a blow, absorb it, and get back on her feet. August 22, 1962, was a high point in my life, and I know it must have been a bad one in yours. But I will always be grateful that the circumstances brought me my daughter. I'm happy for her and for you that you've found each other.... And yes, I would like very much to have a quilt from you, if you'd like making me one....

I press Send before I can fiddle with edits. She replies in two hours.

It is so good to hear from you and to finally "meet" you. Yes, August 22, 1962, was a very sad day for me, and it has been heavy in my heart till December 17, 2004, when I first heard from Joanna. I cannot begin to tell you how thankful I am that she got a great mom like you. I can tell that she is, as you say, remarkable. I'm also glad to know she bounces back. I've had to do that many times in my life....

It feels as if Joanna's on pretty safe ground here. And so, I think, am I.

"They're coming," Jo announces one morning, "May, for a long weekend."

Not Mother's Day, please. Then I say it. "Not Mother's Day."

"No, no, the following weekend." She preempts me on the next touchy point. "I'm finding a motel for them in Danbury—20 minutes away. Easier, don't you think?" Oh yeah, I did think.

"For everyone," I say. Our voices are ramped up—both getting nervous. Weeks away: She will be arriving—not our idea of her. Her.

Joanne and Merrel are to fly in late Thursday night and leave Monday morning. Jo and I brainstorm on the phone daily. Friday will be their day: Jo's and Joanne's; husbands, Jo's sons. Saturday morning Robert and the boys will leave for a long-planned Boy Scout overnight. Joanna has planned meticulously, allowing her and Joanne some alone time. "But not too much," she tells me. "Too much would be hard." She's right, of course.

And where do I fit in?

"Mom, I'd like to bring Joanne and Merrel to you on Saturday—just the five of us." She means our weekend house, 45 minutes from where she lives. We've owned it since Jo was 14. "I've told her about the climbing trees, my hammock down in the valley, the porch view." It pops into my mind that this house is also where on Thanksgiving 11 years ago Joanna miscarried the baby that would have been her third. "Dinner, okay?" she asks. I tell her that sounds fine—and mean it.

Friday comes. Jo's on my mind all day. I've contracted with myself to not call, though I could whomp up a few plausible pretexts. At about 10 P.M., the phone rings.

"Hi, Mom. I'm just driving back from their motel."

A heart skid: "Yes??" My impatient sibilant hisses back in my ear.

"Really good. It was easy, you know? They came loaded with quilts: one for each of the boys in his favorite color and some special thing—like music notes quilted into Steven's. Robert came home early and took Merrel around the grounds so I got time with Joanne. She said again how hard it was for her, giving me up." An undertone in her voice confirms that, diverse as the millions of adopted children are, this they have in common: the need to hear and hear again that they were not relinquished easily. "We're so similar in some things—like the way we use our hands when we talk. She noticed that and—"

Before I can stop myself, "Well, so do I use my hands—and Grandma did, and...everyone in New York."

"But she and I do it the same way." Joanna is right to be pissed with me. She's giving me straight-from-the-heart stuff, which I zap in a flash of jealousy.

"So how do you feel when those similarities pop up?" I'm truly penitent, anxious to get back on track. I am her mother, a supporter, not a contestant.

"Weird but good weird. Like putting in a puzzle piece that fits. Kind of..."

Saturday, finally. Antsy is an understatement. Jo said they'll come on the early side, maybe 6. I get everything pre-prepared. Nothing adventurous: broiled chicken, potatoes, light on the salad with Joanne's Crohn's in mind. When I ask Eamon for the fourth time whether we have enough soda, beer, just in case...he says, "Honey, it'll be fine. Why don't you sit on the porch and get lost in a book?" Right!

At five past 4, the phone rings. "Okay if we come in, like, half an hour?" I parse Jo's voice for trouble and hear none—just eagerness. So. Now. My throat lumps up so I can hardly answer.

"Fine, we'll be waiting for you." My voice is steady—with some effort.

Fifteen minutes later, I hear her van crunch the gravel of our long, winding driveway. I stand at the living room window for a moment watching the three of them get out and then dash down the steps to join them.

At five past 4, the phone rings. "Okay if we come in, like, half an hour?" I parse Jo's voice for trouble and hear none—just eagerness. So. Now. My throat lumps up so I can hardly answer.

Two leggy blue-eyed blondes with pointy-chinned oval faces stand side by side: In 25 years or so, Joanna will look just like the woman who gave birth to her. Joanne's wearing tweedy cotton pants and a green sweater with a small gold ornament on a chain round her neck (reflex, I check: it is not a cross). The clothes are very much the kind of thing Jo wears—I think of them as Midwestern: me, ever the New York provincial in my black and more black. None of the three of us is overweight, but they carry theirs around the middle while I carry mine below: two blonde apples and a brunette pear. All of this takes a shaved second to race through my mind as my eyes mist. My daughter opens her arms. We hug fast and tight.

"Pretty as a picture," Joanne says, meeting my eyes, smiling. I can't tell whether she means the house, the landscape, Joanna, or me.

"Welcome," I respond, exchanging ceremonial embraces with her and Merrel. By now Eamon is beside me. Merrel is stocky and pleasantly blunt-faced—the kind of guy you hope is around when your ceiling falls down because he'll know what to do. In fact, he looks like the retired sailor he is, complete with small tattoo. I like him.

They begin to unload quilts from the back of the van. Andrew's in green and white with a raised pattern; Steven's yellow with the music notes Joanna mentioned; Thomas's bright red. Here's one Merrel made, striking and modern. And last, here's mine. Joanne and Jo hold it way up: butterflies, each different from the other, some centered inside mossy grids, a few escaping. She tells me it's called Butterflies Are Free. I tell her it's a piece of art. I tell her I love it.

After Jo shows them around, we convene on the porch. They'd like a drink (thank God; I'm dying for one). Jo stays nonalcoholic. She never took to drinking, hated the taste and the feeling. An innate alarm system: potential danger on the paternal side?

The weather looking west toward the Catskills is cooperating: just warm enough to stay comfortable outdoors. Joanne talks of her ancestors. From Scotland and Germany, they began to come in the 17th century, landing in Twin Falls, Idaho. I think of my grandma, who arrived at Ellis Island from Lithuania in the 20th, and who referred to any immigrant 50 years before her as a Yankee Doodle. I don't chime in with this but ask more questions, caring less about the answers than about keeping the ball in play. Joanna is staying on the sidelines, but when I steal a glance, her face says so far, so good.

I ask how Joanne and Merrel met and learn that she had returned to Idaho to nurse her dying mother, while he, living next door, was nursing his dying wife. After the deaths, they got into a van and just drove, stopping in places that appealed. A small town outside Eugene won their hearts, and there they settled. It's something Eamon and I might have done—did in the case of the house we sit in right now. Merrel keeps his eyes mostly on Joanne. You'd have to be blind to miss how much he cares for her.

She brings up her relationship with God. "I talk to him, just straight, and he always understands and helps. I'm really very religious." Joanna and I exchange looks: We don't go there. I'm a cultural Jew with no religion as such; this is how Jo was raised and what she cleaves to. I say, "It must be really comforting to you" ...or something similar.

Actually, what she's just said about God reminds me of an e-mail in which she'd quoted a life lesson from her adored late father about dealing with a problem: "Think it through, and if there's something to do, do it right now. If there's nothing, forget it and don't worry, because no amount of worry will cure it. So that's how I've lived my life." Which, if literally true, makes her the most worry-free human I've ever met.

But a moment later, I see it's not precisely true, because she turns to me and says, "You know when that man killed his adopted little girl?"

"You mean Joel Steinberg?"

She nods. "I was worried sick then. I mean, they told me at the hospital that my baby was going to a very good home—a doctor and his wife. And that made me feel...easier. But how can anyone really know? Steinberg was a lawyer and rich. They must've told that baby's mother..."

Sympathy floods me. "Yeah," I murmur. Triggered by mention of Steinberg, my head fills with another child-centered story, as iconic a nightmare for me as Steinberg had been for Joanne: a Chicago toddler, snatched, screaming in terror, from his adoptive mother's arms—by court order. This because his birth father had never known of his existence, so had not given his consent to the adoption. Now reunited with his old girlfriend, they felt entitled to "their son." Incredibly, the Illinois Supreme Court (overturning lower-court decisions in favor of the adoption) ruled for ties of blood over ties of life and removed the child from the only home he'd ever known.

One coin; two sides. What is a mother? I know what the word means to me, but I'm hardly neutral on the question. A couple of weeks ago, Jo and I were discussing the language of adoption: birth mother (this itself a p.c. improvement on real mother or natural mother); adoptive mother. We both allowed as how we find all the modifiers deficient. "You're just my mom." She thinks her sci-fi books have it right. "They invent language for precision—maybe a word like birther or...something."

Now Jo comes into the kitchen to help put dinner on the table. She gives my arm a small squeeze; I give her a big grin in exchange. As we eat, the conversation takes on the ease of distant relatives catching up. We talk about Joanna's boys, about travel, about...the things people talk about. As I glance around the table, it occurs to me that Joanne and I between us account for at least seven marriages. Unlike us, Jo has had just the one, which I believe will be her only—a reminder that people take the nature/nurture clay and mold themselves.

When we adjourn to the living room, it's already past 10—and no one seems remotely ready to call it a night. Joanna, looking as pleased as a well-stroked cat, asks, "Should I go to the car and get the supplies for the quilt?" Another quilt?

"It's one I'd love to do, if it's okay," Joanne says. "I want to get the whole family's handprints: Joanna, Robert, the boys, you and Eamon. I've got indelible finger paints, pens, cotton squares. Everybody leaves a handprint and signs it. So...would you? Uh, Merrel and I don't have to be on it ourselves...."

"Of course you'll be on it," I say. I know it's what I'm supposed to say, but in the spirit of the evening, there's no question I mean it.

We make our squares, clean up, talk some more. I give her a copy of my latest novel, which she asks me to sign. When Jo announces it's a quarter to midnight, we all stand up. Joanne and I look at each other and say almost in chorus, "Thank you." I see that Merrel's eyes are teary and realize mine are, too. The evening ends with embraces; real ones.

The following Tuesday, I e-mail Joanne telling her how we enjoy Butterflies Are Free draped across the foot of our bed; how glad we were to have met them. Two hours later, a response:

...I thank you again for raising such a lovely daughter and bestowing her with so much love. I could not have picked a better mother for her had I searched the entire world over.

Life stories only end at life's end, and this one's nowhere near over. So far our story has been better than good, and the glow I see in my daughter is not only pride in her newly won black belt. At the moment, I have nothing to add, only to echo: Thank you. ?

For the Oprah Magazine or download The Adoption Papers

Carol Brennan Novels

Writing As Caroline Slate

Reviews

This unusual, interesting novel is well crafted and suspenseful. Grace is an appealing and sympathetic character. Romantic Times Book Club

News

- A Story For Eamon "The Train You Get Lost On"

- A Conversation - an in depth look at the book The House On Sprucewood Lane.

- Read the The Adoption Papers online, at Oprah Magazine or download it.